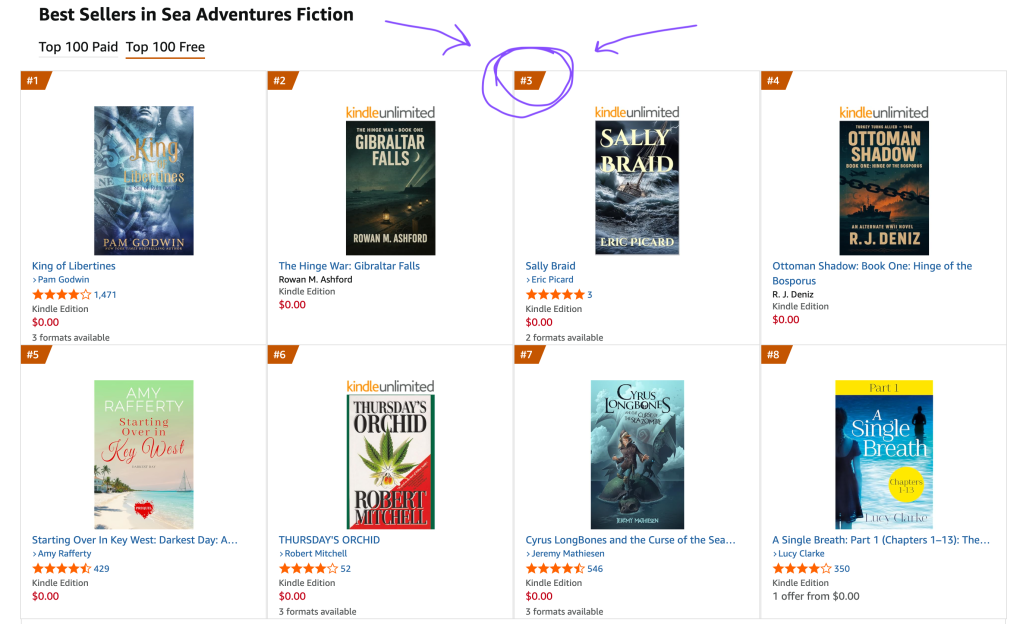

My short story, Sally Braid is free on Amazon for ONE MORE DAY!

Please get your free copy now. It hit number 3 in Sea Adventure Fiction today. And you can add an audiobook version for just $1.99!

I wrote the first version of Sally Braid in graduate school, and rewrote it just a few years ago. Below is the new Afterword that I just added to it, should be live in the eBook version later today or tomorrow.

—

I had been a commercial boat captain during the summers, all through college and graduate school. I drove launch tenders, boats that take people from shore out to their boats on moorings and anchors, in Newport, Rhode Island. The launches were 26 feet long, could take about 20 passengers. It was an amazing summer job, one where I learned not only how to handle boats incredibly well, but where I learned a lot about people. I drove the launch in all sorts of conditions, including once in a hurricane (without any passengers.)

One night in early September before going to graduate school, I was tied up at the dock while an unforecasted squall came through, much like what Tess experienced. During the peak of the storm, with lightning striking all around the harbor, I got a call on the radio from the Harbor Master. He was trying to rescue a boat that had broken loose when the squall line came through. He was a young guy, a junior Harbor Master, and had very little experience towing boats, and was getting dragged towards the rocks at the Ida Lewis Yacht Club. I reluctantly left the dock in 50 knots of wind, with driving rain, lightning and thunder going off all around me.

It was the first time in my life that I was so close to lightning strikes. The hairs on my arms were standing up with static electricity just before the lightning strikes. The air was lasing purple, and I saw St. Elmo’s Fire, the corona effect ahead of lightning strikes, on tall boat masts around me. The sound of the thunder was so loud that I felt it in my chest, the only other time I’ve felt anything like that was being close to fireworks going off. I imagine it must be similar to be in artillery fire. My 57 year old brain thinks my 23 year old self was a moron for going out, but the memory of the panicked, pleading sound of the Harbor Master’s voice reminds me that I needed to go.

When I got to the Harbor Master, he had caught a 70 foot classic wooden yacht that had broken loose from its mooring. He had tied off too far forward on the boat and couldn’t stop it from dragging. I tied off properly on the other side of the boat, and I got the yacht under control. As I tied the launch off, a wave came up and went right down the front of my foul weather gear, and my only thought was that the ocean water was so warm, much warmer than the air and rain.

We got the boat across the harbor and tied off on another mooring. The Harbor Master thanked me and said he owed me a beer. I told him he owed me his firstborn child.

Tess is an amalgam of several of my customers, but two in particular. One was a woman who was as hard as nails, an avid sailor who had Olympic aspirations in her twenties, but never made it. She sailed with her husband on their yacht, racing all over New England. Everyone thought it was her husband who was the great sailor, and they won a lot of races. In reality, while he ‘drove’ the boat, it was his wife who was the tactician and navigator, and really ‘ran’ the boat. I asked her once if it bothered her that nobody realized that she ran the boat, and she smiled an uncharacteristic smile, but didn’t answer. They were in their fifties, about my parents’ age at the time. To me they were an older couple, but were actually younger than I am right now. Time changes perspectives.

I had another customer who was Tess’s age, in her seventies, who had lost her husband the previous year. She had spent decades on their boat, a classic wooden trawler, which her husband had meticulously maintained. But she herself always relied on her husband to take care of everything. She barely knew how to drive the boat, and didn’t know how to turn on the engines, run the generator, didn’t understand about bilge pumps, charging the batteries, or that the refrigerator on her boat shouldn’t be left on while on the mooring without shore power.

One night when I was driving by, I noticed that the boat was very low in the water. I knocked on the hull and she came out. We realized the batteries were dead, and the bilge pump was not running. Like many old wooden boats, she had a tiny leak around the shaft that the bilge pump normally kept up with easily. But since the batteries were dead, the pump wasn’t running and the boat was slowly sinking. I helped her start the generator, and showed her how the different battery switches controlled where the power went, from which batteries. All very mundane stuff, but rather critical to understand when living on a mooring.

She was very sweet and sad, and the launch drivers took her under our wing and helped her out with everything. By the second week on the mooring she had learned every hard lesson she needed to learn about what not to do. Undaunted, she stayed on the boat all summer long, into the Fall. She slowly became more confident. One evening when it was very quiet and slow, she invited me swing by for dinner and I tied the launch up next to her boat and we talked for a bit.

As we ate, I asked her why she’d decided to stay on the boat that summer, and she got very quiet, and shyly said, “It’s the only place I still see him.” The hairs on my arms went up, just like they did that time from St. Elmo’s Fire.