The month my father and my brother both died

An Essay by Eric Picard

On July 18, 2017, I experienced a life threatening injury. Then, on July 19, 2020, I had another life threatening injury. Given these life-threatening incidents, you might understand why after another three years plus one day, I felt apprehensive as July 20, 2023, approached.

Strangely enough, terrible three-year cycles had happened in my family before. When my brother was three, he fell down the cellar stairs and had to go to the hospital for stitches. At six, my cousin and I knocked down a dead tree in the woods, and my brother stepped right into its path, resulting in another trip to the hospital for stitches. At nine, he lost his balance and fell down a hatch on our step-father’s navy ship, once again requiring stitches. The pattern continued at twelve, fifteen, and eighteen, with various injuries culminating in a spleen rupture at eighteen and more stitches at twenty-one. By then, I had stopped keeping track.

So, on Thursday, July 20, I was understandably anxious. Fortunately, the day passed without any health emergencies. On Sunday, July 23, I drove up to East Wareham, Massachusetts to pick up my dad for a lunch date with two of my daughters.

Upon arrival, I noticed something was off. His car was parked at a strange angle, and newspapers had accumulated on the porch — highly unusual for someone who read the paper religiously every day. Inside, I ominously found a small pool of dried blood on the kitchen floor.

When I stepped outside, the next-door neighbor approached to deliver the sad news: my father had been found dead the day before, and no one had my contact information.

After a moment of grief, I composed myself on the front steps. The newspapers on the porch included the Friday, Saturday and Sunday editions, and inside, the Thursday paper from July 20 was opened but folded neatly on the sofa. He had died on the 20th. So I hadn’t quite emerged unscathed from the pattern.

I need to clarify something: I loved my dad and I miss him dearly. But he was 85 years old, smoked two packs of cigarettes a day since he was 16, and drank a six-pack of beer daily. While his sudden death was upsetting, it wasn’t entirely surprising given his age, health and lifestyle. It was likely an aneurysm, and at least it was fast and relatively painless.

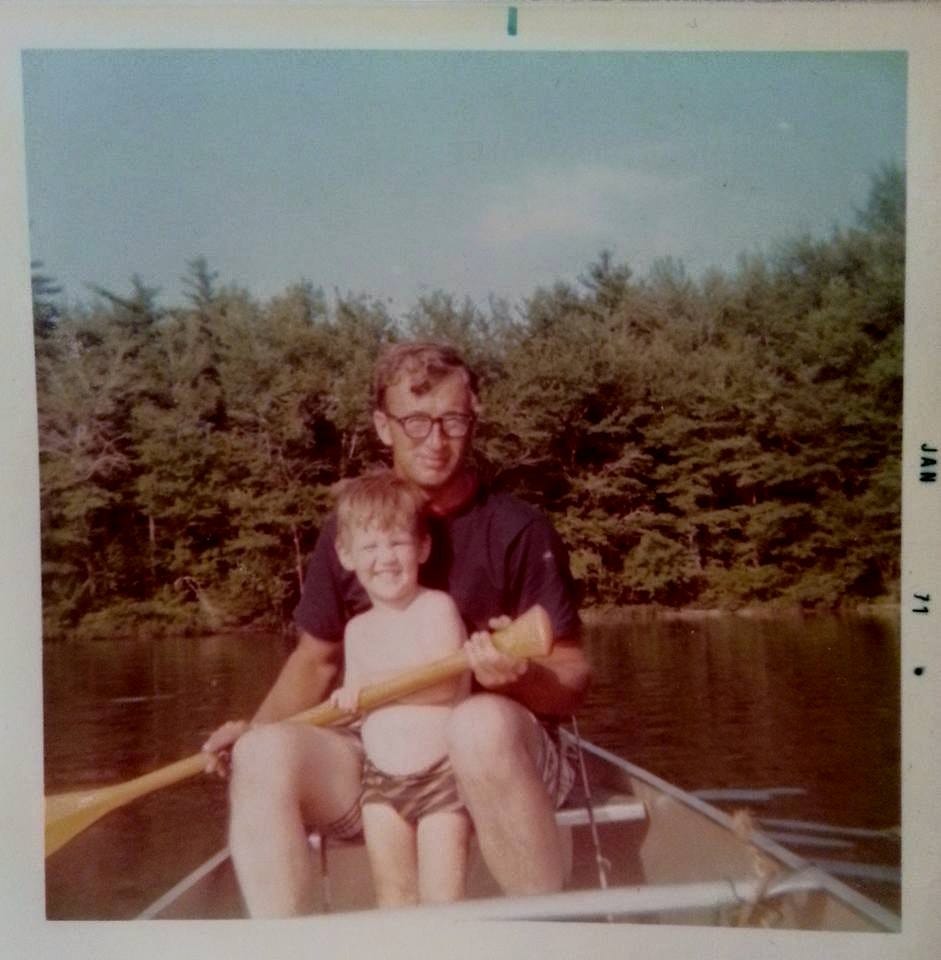

My dad had worked early on as an engineer developing early computer chips. He then started a roofing and construction company that he ran for many years. Then he moved back to electrical engineering quality assurance work until he finally retired. He was an avid hunter in his younger years, favoring pheasant and rough grouse. He loved to fish. He loved cars. And he taught me to love skiing.

One of the hardest things I had to do that day was call my brother to inform him of our father’s death. But first, some backstory is necessary.

My brother, Jeff, is a challenging person. In Reddit terms, he’s definitely TA. Jeff had been struggling with bipolar disorder since his mid twenties, and for the last six months had been struggling with MS, affecting his balance and mobility. He’s also always been difficult, even abusive. Jeff had lived with our father for the past 15 years, despite the retirement community’s rules prohibiting residents under 55. Their relationship was tumultuous, to say the least.

Jeff was often in trouble with the police, frequently went off his meds, and had a history of violent behavior, towards strangers, and towards our father. My dad had been airlifted for emergency brain surgery after one of those attacks. Jeff spent time in prison several times. My brother and I were estranged, and other than periodic nasty voicemails left for me, we hadn’t spoken in years.

Jeff’s voicemails typically started with, “Hey, it’s your brother. I’m really sad that we don’t have a relationship — I want my big brother back. I really love you, and I miss you… but you know, you’re an asshole. I’m gonna come to your house and beat you in front of your kids.” They generally deteriorated from there.

For the last few months of our father’s life, Jeff wasn’t living with him, which brought me a bit of comfort through all of this. He had been in the hospital and physical rehab for his MS, and upon his release, he flew to Arizona to see his son but ended up hospitalized again. He’d been there for a month when our father died.

So, I called Jeff to break the news. The call went something like this:

“Hi Jeff, it’s Eric. I hate to have to tell you this, but Dad died.”

“Oh, that’s terrible. That’s horrible.”

“Yeah, I’m really sorry to have to call you with this news.”

“Wow… That’s really terrible. He was supposed to pick me up at the airport next week. Now how am I getting home?”

That should give you a flavor of the situation.

That week I went to the state medical examiner’s office and met Alice, a kind investigator, to identify my father officially. She was a professional, and very kind. Dad looked surprisingly good given the circumstances. Peaceful.

The Saturday following my phone call, Jeff flew back to Boston and took an Uber to our dad’s home. In the meantime, I was dealing with the estate, which consisted of very little. Dad had signed over his extremely modest mobile home and his car to me several months before he died when Jeff went into the hospital.

Our dad wanted Jeff to be able to live in his mobile home, but Jeff wasn’t yet 55, and there were restraining orders against him from the retirement community my dad lived in. I started working with a lawyer, but we couldn’t find a clear path forward. Despite everything, Jeff is my brother, and I felt some empathy for his situation, and I wanted to honor my father’s wishes to keep him from becoming homeless.

The lawyer needed to speak with Jeff, so on Sunday after he had returned home, I called him but got no answer. On Monday, I was scheduled to pick up our dad’s cremation remains. I left a message for Jeff, saying I’d come by to talk to him.

After picking up our dad’s remains and having a surprisingly light-hearted conversation with the funeral home director, I drove over to my dad’s place. When Jeff didn’t answer the door, I let myself in and found him on the floor, holding a picture of our dad. He had died shortly after arriving home on Saturday.

The scene was eerily similar to a nightmare I had on Saturday night (the night he died), where I found Jeff in that exact position, in that exact location. I had been dreading what I was going to find since he hadn’t answered my calls.

I called the police and waited on the front steps. When they arrived, one officer asked, “Who is inside?”

“My brother,” I replied.

“Jeffrey’s inside? I thought he was away in Arizona!” he exclaimed. They went inside and verified that my brother was dead, and also that it was my brother. Then we sat and waited for the medical examiner’s office, and had a long conversation about all the history that my brother had with the police. Despite how difficult he had been for me, and for them, they showed some genuine affection for him. My brother had been a very charismatic and funny guy, even in his mania.

The rest of the morning was a blur, but I managed to call the funeral home from the car. The director was shocked to hear from me so soon, and I asked, “Is there any chance you have a two-for-one special on cremations?” I explained about my brother. He was horrified for a moment, but then he quickly saw the dark humor in the situation. I find that Funeral Home Directors have seen it all, and generally have to have a decent sense of humor.

Another difficult call was to my aunt, our dad’s sister. She was shocked to hear about Jeff, and said, “Well, at least he’s with your father.”

I replied, “Oh no, Dad’s only had two weeks!”

A few days later, I received a call from the state medical examiner’s office. “Hi Mr. Picard, my name is Alice, from the state medical examiner’s office.”

“Oh, Alice — so good to hear from you again!” I said.

“Uhm… What?” she replied, confused.

“I met you last week! I’m glad it’s you calling.”

“Uhm, where did you meet me?”

“In your office in Sandwich. Oh, I know you’re calling me about my brother, Jeffrey, but last week I was in your office to identify the remains of my dad, Eugene.”

There was a ruffling of papers and a gasp. “Oh my God, I’m so sorry. I didn’t connect the names. I’m so sorry, this is the most horrible thing that’s happened to me in this job!”

I reassured her, “Oh Alice, I can’t imagine that’s true. It’s hard to believe that this is the worst thing you’ve experienced at work, based on what your job is. But it’s kind of you to say so.”

We had a nice chat.

The thing about the death of my dad and my brother is that I’m at peace with my father’s death. He lived a long life, and the last 15 years were really chaotic for him with my brother living there.

While I’m not at peace about my brother yet, I’m finding a path toward it. When you’re estranged from someone for literal safety reasons, you’re always on edge that they’ll show up and fulfill their threats. Now that this has ended, something interesting has happened.

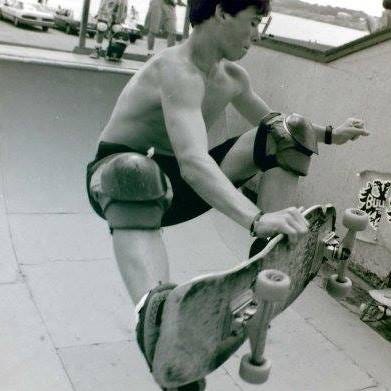

I can suddenly unlock the good memories of my brother from our childhood. We were really close as kids. He was a great skateboarder and surfer, and I was secretly proud of his abilities there. When people share stories about how funny he was in high school, I can actually appreciate it. For me, the feelings of healing from this loss have to do with an unclenching. When it came to my brother, I carried around a tightness, a clenching of my heart, my back, my neck. I was always on edge where Jeff was concerned. But now that tightness is loosening. And I can see a glimmer of what a healed connection to my brother, in his death, will ultimately look like.

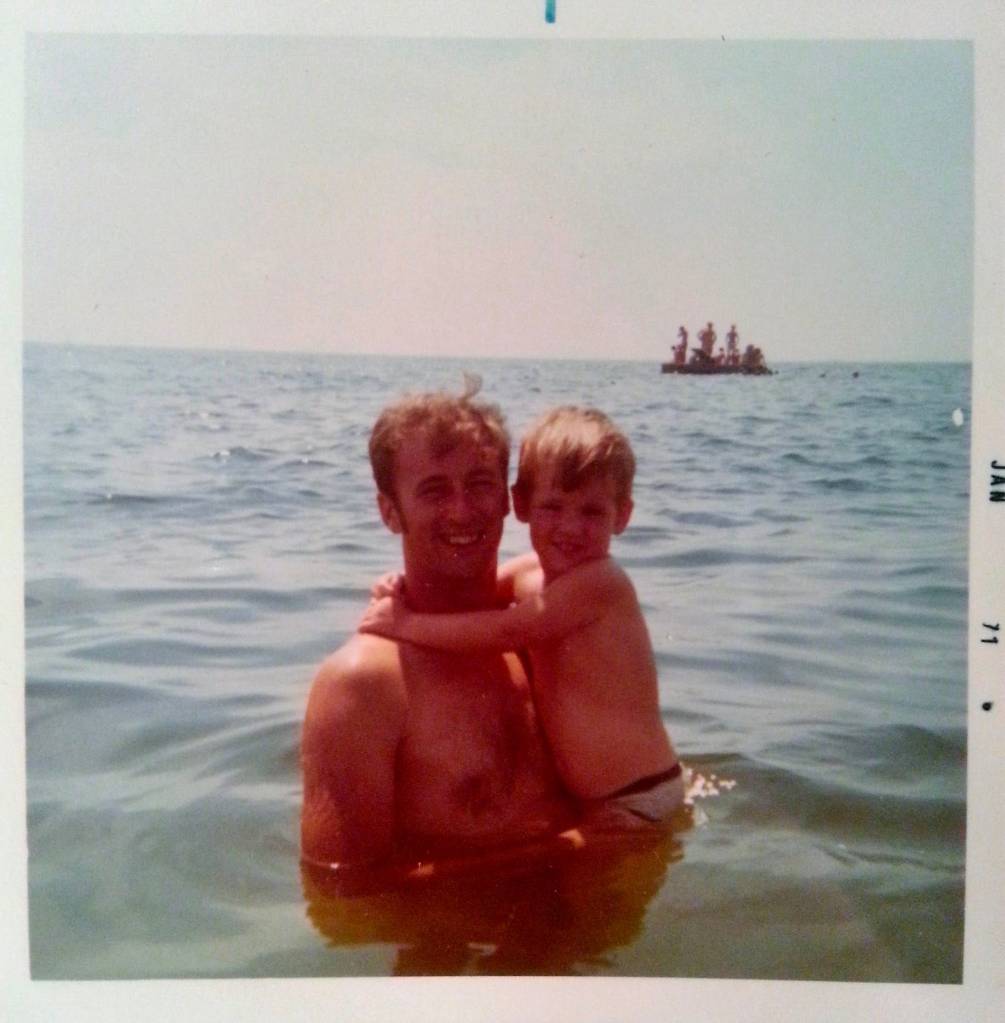

I miss my dad. It catches me unaware, at odd times. I’ll think of him, and feel my breath catch. But I’m at peace with my father. We had a little ceremony for him on the beach he grew up swimming at. Dad loved that beach, and had a deep fondness for this one spot in particular. And we let him go there. Something unexpected happened to me last summer after his funeral. When I went swimming afterwards, I felt super connected to him through the ocean. I felt like we shared the gulf stream, and that we shared the tides, and that we shared a new connection. Rest in peace, Dad.